MEXICO

CEDAW Optional Protocol Article 8 Examinations Concerning Gender Discrimination

CEDAW A/59/38 part II (2004)

CHAPTER V

B. Action taken by the Committee in respect of issues arising from article 8 of the Optional Protocol

390. In accordance with article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol, if the Committee receives reliable information indicating grave or systematic violations by a State party of rights set forth in the Convention, the Committee shall invite that State party to cooperate in the examination of the information and, to this end, to submit observations with regard to the information concerned.

391. In accordance with rule 77 of the Committee’s rules of procedure, the Secretary-General shall bring to the attention of the Committee information that is or appears to be submitted for the Committee’s consideration under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol.

392. In accordance with the provisions of rules 80 and 81 of the Committee’s rules of procedure, all documents and proceedings of the Committee relating to its functions under article 8 of the Optional Protocol are confidential and all the meetings concerning its proceedings under that article are closed.

Summary of the activities of the Committee concerning the inquiry on Mexico

393. By letter dated 2 October 2002, Equality Now, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council, and Casa Amiga, a rape crisis centre in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, submitted information containing allegations of the abduction, rape and murder of women in the Ciudad Juárez area of Chihuahua, Mexico, in particular that, since 1993, more than 230 young women and girls, most of them maquiladora workers, had been killed in or near Ciudad Juárez. The organizations requested that the Committee undertake an inquiry concerning Mexico.

394. No information shall be received by the Committee if it concerns a State party which, in accordance with article 10, paragraph 1, of the Convention, declared at the time of signature or ratification of the Optional Protocol that it did not recognize the competence of the Committee provided for in articles 8 and 9. Mexico ratified the Optional Protocol on 15 March 2002 without making such a declaration. The Procedure under article 8 could, therefore, be applied to Mexico.

395. During its twenty-eighth session (13 to 31 January 2003) the Committee, pursuant to article 82 of its Rules of Procedure, requested two of its members (Ms. Yolanda Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Maria Regina Tavares da Silva) to examine the information provided and other available information and, in the light of their examination, the Committee concluded that the information provided by Equality Now and Casa Amiga was reliable and that it contained substantiated indications of grave or systematic violations of rights set forth in the Convention. The Committee decided to invite the Government of Mexico to submit observations with regard to that information by 15 May 2003. The Government of Mexico submitted observations on 15 May 2003 and further observations on 7 July 2003. On 3 June 2003, Casa Amiga, Equality Now and the Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights submitted additional information to the Committee.

396. At the Committee’s twenty-ninth session (30 June to 18 July 2003) the Committee decided to conduct an inquiry. It designated the same two of its members to visit Mexico and to report to the Committee confidentially at its next session in January 2004.

397. On 11 August 2003, the Government of Mexico was informed of the Committee’s decision to establish an inquiry, and was requested to consent to a visit by the two members designated by the Committee. On 27 August 2003, the Government of Mexico agreed to the visit, confirmed Ms. Patricia Olamendi, Vice-Minister for Global Issues in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as its designated representative for the inquiry, made a commitment to provide all the assistance necessary to ensure that they could carry out their mission properly and agreed that the visit take place from 18 to 26 October 2003. From the outset, the Government of Mexico showed a willingness to cooperate fully with the Committee.

398. The two designated members of the Committee carried out the inquiry on the aforementioned dates. They visited the Federal District and State of Chihuahua (Chihuahua City and Ciudad Juárez) during the visit to Mexico.

399. In the Federal District, Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva met with the Ministry of the Interior (Head of the Human Rights Promotion and Protection Unit, Deputy Director-General of the Unit and Adviser to the Under-Secretary for Human Rights), Ministry of Development (SEDESOL) (Minister, Under-Secretary for Urban Development and Land Management and Director-General of the Institute), Federal Government Commissioner for the cases of women in Ciudad Juárez, Public Prosecutor’s Department/Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic and three Deputy Attorneys-General (Organized Crime, Regional Control, Protection and Criminal Proceedings and International Affairs) and the Directors-General of the Office of the Attorney-General (Crime Prevention, Victim Support), the National Women’s Institute (INMUJERES) (Chairperson of the Institute, Technical Secretary, Coordinator for Advisers and Deputy Director-General for International Affairs), National Human Rights Commission (Second General Representative), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Under-Secretary for Global Issues and Human Rights, Adviser to the Under-Secretary and Deputy Director-General of the Directorate-General of Human Rights). The members of the Committee also met with nine representatives of the Special Committee of the Senate to Monitor the Murders of Women in Ciudad Juárez, five representatives of the Commission on Equity and Gender of the Chamber of Deputies and the Subcommission of Coordination and Contact to Prevent and Sanction Violence against Women in Ciudad Juárez. The experts also met with United Nations bodies (the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM)) and non-governmental organizations (Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights and Milenio Feminista).

400. In the capital of the State of Chihuahua, the members of the Committee conducted interviews with the interim State Governor and Secretary-General of the Government, the Assistant State Public Prosecutor and the Director of Legal Affairs of the Office of the Public Prosecutor. They also called on the Head of the Chihuahua Women’s Institute.

401. In Ciudad Juárez, Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva held interviews with joint State/Federal, Federal and municipal authorities together with associations of the mothers of the women murdered or abducted in Ciudad Juárez or Ciudad Chihuahua, mothers and other relatives of victims and representatives of civil society. They visited sites where numerous victims’ bodies had been found in 2001 and 2002/3, sites of maquiladoras and the poorest areas of Ciudad Juárez. They interviewed the Assistant State Public Prosecutor for the northern Region, the Special State Prosecutor (Joint Office of the Prosecutor for the investigation of the murders of women), the Personal Assistant to the Mayor, the Representative of the Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic, the Head of the Federal Section of the Joint Agency for the Investigation of the Murders of Women and the General Coordinator for Human Rights and Citizen Participation of the Ministry of Public Security (Preventive Federal Police).

402. In Ciudad Juárez, the two experts also met with organizations of the victims’ relatives and mothers of victims (Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, Justicia para Nuestras Hijas, Integracíon de Madres de Juárez), local non-governmental organizations (Red Ciudadana No Violencia y Dignidad Humana, Casa Promoción Juvenil, Organización Popular Independiente, CETLAC, Grupo 8 de marzo and Sindicato de Telefonistas) and representatives of the local, national and international non-governmental organizations Casa Amiga, Equality Now and the Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights.

403. On 23 January 2004 during its thirtieth session (12-30 January 2004), the Committee, after having examined the findings of the inquiry, adopted its report including conclusions and recommendations addressed to the State party. Pursuant to article 8, paragraphs 3 and 4, the findings, comments and recommendations of the Committee were sent confidentially to the Permanent Representative of Mexico to the United Nations in New York with a request that the Government of Mexico submit observations thereon within six months of receipt.

404. On 21 July 2004, during its thirty-first session (6-23 July 2004), the Government of Mexico submitted its observations to the Committee. The Committee also received supplementary information from Equality Now, dated 7 July 2004. The Committee designated Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva to examine the observations and additional information and to report thereon to the Committee.

405. Having considered the Government’s observations the Committee decided, in accordance with article 9, paragraph 2, of the Optional Protocol, to invite the State party to submit, by 1 December 2004, a detailed report on steps taken, measures implemented and results achieved in relation to all the recommendations of the Committee contained in the Committee’s findings transmitted to the State party on 23 January 2004.

406. All activities of the Committee or its designated members in relation to this inquiry were carried out in strict compliance with the relevant confidentiality provisions of the Optional Protocol and the Committee’s rules of procedure.

407. The Committee noted that it will consider follow-up measures taken by the Government in response to its inquiry at its thirty-second session (10-28 January 2005).

408. The Committee decided that it would issue a summary of its findings and recommendations and the Government’s response at a future date.

CEDAW A/60/38 (Part I) (2005)

Chapter V

Activities carried out under the Optional Protocol to the Convention

33. Article 12 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women provides that the Committee shall include in its annual report under article 21 of the Convention a summary of its activities under the Optional Protocol.

A. Action taken by the Committee in respect of issues arising from article 2 of the Optional Protocol

34. The Committee took action on communication 2/2003 (see annex III to the present report).

B. Action taken by the Committee in respect of issues arising from article 8 of the Optional Protocol

35. In accordance with article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol, if the Committee receives reliable information indicating grave or systematic violations by a State party of rights set forth in the Convention, the Committee shall invite that State party to cooperate in the examination of the information and, to this end, to submit observations with regard to the information concerned.

36. In accordance with rule 77 of the Committee’s rules of procedure, the Secretary-General shall bring to the attention of the Committee information that is or appears to be submitted for the Committee’s consideration under article 8, paragraph 1, of the Optional Protocol.

37. The Committee continued its work under article 8 of the Optional Protocol during the period under review. In accordance with the provisions of rules 80 and 81 of the Committee’s rules of procedure, all documents and proceedings of the Committee relating to its functions under article 8 of the Optional Protocol are confidential and all the meetings concerning its proceedings under that article are closed.

38. Pursuant to rule 77 of the Committee’s rules of procedure, the Secretary-General brought to the attention of the Committee information that had been submitted for the Committee’s consideration under article 8 of the Optional Protocol.

Summary of the activities of the Committee concerning the inquiry on Mexico, and follow-up

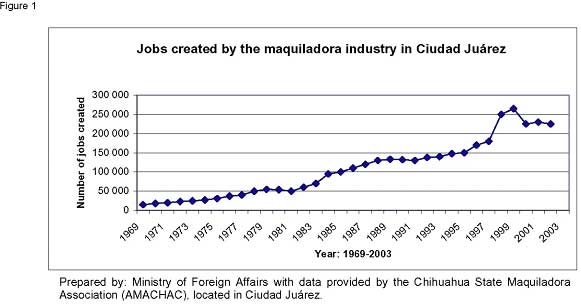

39. The Committee reiterated its decision, taken at its thirty-first session, to issue at a future date the substantive findings and recommendations emanating from its inquiry, in accordance with article 8 of the Optional Protocol, in regard to Mexico, together with the State party’s observations (see A/59/38, part II, chap. V.B). The Committee issued these findings and recommendations, together with the State party’s observations, on 27 January 2005 (CEDAW/C/2005/OP8/Mexico).

40. The Committee recalled its decision requesting the Government of Mexico to submit information, by 1 December 2004, about measures taken in response to the Committee’s recommendations submitted to the State party on 23 January 2004. It received preliminary information on 13 December 2004 and additional information on 17 January 2005. It decided to request the Government of Mexico to submit additional information on follow-up given to the Committee’s recommendations in a succinct report, of up to 10 pages, by 1 May 2005. The Committee further decided to invite the three NGOs that had submitted the information that led to the Committee’s decision to conduct an inquiry under article 8 of the Optional Protocol in regard to Mexico, Equality Now, Casa Amiga and the Mexican Committee for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights, to provide their views in a succinct report to the Committee, by 1 May 2005, on the current situation concerning the killings and abductions of women in the Ciudad Juárez area of Mexico, and in particular their evaluation of the State party’s actions in response to the Committee’s findings and recommendations. The Committee decided to consider Mexico’s follow-up response, together with any information that might be received from the NGOs, at its thirty-third session, scheduled to take place from 5 to 22 July 2005.

CEDAW/C/2005/OP.8/Mexico (2005)

Report on Mexico produced by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention, and reply from the Government of Mexico

At its thirty-first session in July 2004, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women concluded an inquiry under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in regard to Mexico that also included a visit to the State party’s territory. The Committee included a procedural summary of the inquiry in its annual report (A/59/38, Part II, Chapt. V.B). It decided to make public at a later date its findings and recommendations regarding the abduction, rape and murder of women in the Ciudad Juárez area of Chihuahua, Mexico, as well as the observations received from the Government of Mexico thereon.

The present document is being issued pursuant to that decision and is divided in two parts. Part one consists of the Report of the Committee – findings and recommendations. Part two contains the observations of the Government of Mexico on those findings and recommendations.

Contents

Part one

Report of the Committee – Findings and recommendations

I. Introduction

II. Visit to Mexico, 18-26 October 2003

Activities of the members of the Committee during the visit

General conditions for the visit

III. Gender-based discrimination and violence — the situation in Ciudad Juárez

General context and evolution of the situation

Different forms of gender violence — data, characteristics and initial reactions

Repetition of the phenomenon in other areas

International commitments in the field of women’s rights

IV. Murders and disappearances

Principal problems

Profile of the murdered and disappeared persons

Circumstances in which the bodies are found

The disappeared

Investigations and trials

Hostile attitude towards family members and the situation they face. Threats and defamation directed towards civil society organizations

Lack of confidence in the justice system

Inconsistent data

Impunity

Transfer to the federal level

V. Responses by the Mexican Government: policies and measures

Responses in the early years

Programme of collaborative action by the federal Government to prevent and combat violence against women in Ciudad Juárez

(a) Activities related to the administration of justice and the prevention of crime

(b) Activities related to social advancement

(c) Activities related to human rights of women

Coordination and Liaison Subcommission for the prevention and eradication of violence against women in Ciudad Juárez

Evaluation of the implementation of the Programme

Specific actions of the state and municipal authorities

(a) Legislative amendments

(b) Other actions

Commissioner for the Prevention and Punishment of Violence against Women in Ciudad Juárez

VI. Contributions of civil society organizations

Principal complaints and demands

Incompetence of the authorities

Action taken by non-governmental organizations

Assessment of the role of CEDAW

VII. Conclusions and recommendations

A General Recommendations

B Recommendation concerning the investigation f the crimes and punishment of the Perpetrators

C Preventing violence, guaranteeing security and promoting and protecting the human rights of wmen

Part two

Observations by the State Party – Mexico

Acronyms used

Introduction

1. Economic, political, social, gender and crime context in Ciudad Juárez

2. Action to eliminate discrimination against women in Mexico and international human rights obligations

3. Progress, obstacles and challenges facing the Government of Mexico in respect of the murders and disappearances of women in Ciudad Juárez

3.1 Situation of women in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua

3.2 Progress in responding to this situation with the support of international organizations

3.3 Progress made by the Government of Mexico in the promotion of human rights and social development

3.4 Progress made by the Government of Mexico in terms of investigation and prosecution

3.5 Specific cases involving requests by the Committee experts

4. Obstacles and challenges

5. Measures to be taken in future in response to the Committee’s recommendations

Conclusions

Part one

Report of the Committee – Findings and recommendations

I. Introduction

1. In accordance with article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, if the Committee receives reliable information that, in its opinion, indicates grave or systematic violations by a State Party of the rights set forth in the Convention, the Committee shall invite the State Party to cooperate in the examination of the information and, to this end, to submit observations with regard to the information received. Subsequently, the Committee may designate one or more of its members to conduct an inquiry and report urgently to the Committee. Where warranted and with the consent of the State Party, the inquiry may include a visit to its territory. All actions carried out by the Committee shall be confidential and the cooperation of the State Party shall be sought at all stages of the proceedings.

2. Mexico ratified the Optional Protocol on 15 March 2002. Therefore, the procedure set out in article 8 of that Protocol is applicable to Mexico.

3. In a letter dated 2 October 2002, the non-governmental organizations Equality Now and Casa Amiga, located in New York, United States of America, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, respectively, requested the Committee to conduct an inquiry, under article 8 of the Protocol, into the abduction, rape and murder of women in and around Ciudad Juárez, State of Chihuahua, Mexico, in order to reinforce the support it had already given to the case following its examination of Mexico’s fifth periodic report, submitted in implementation of the Convention at its exceptional session in August 2002 (in its observations, the Committee had expressed particular concern at the apparent lack of results of the investigations into the causes of the numerous murders of women and the failure to identify and bring to justice the perpetrators of such crimes and called on the State party to promote and accelerate compliance with Recommendation No. 44/98 of the Mexican National Human Rights Commission in relation to the investigation and punishment of the Ciudad Juárez murders). The two non-governmental organizations provided specific information about the issue.

4. At its twenty-eighth session (January 2003), the Committee, pursuant to article 82 of its Rules of Procedure, requested two members of the Committee (Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva) to undertake a detailed examination of the information provided. The two experts carried out that examination in the light of other information available to the Committee, in particular the relevant conclusions of the other treaty bodies and the reports of the United Nations Special Rapporteurs on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and on the independence of judges and lawyers. In the light of the examination carried out by Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva, the Committee concluded that the information provided by Equality Now and Casa Amiga was reliable and that it contained substantiated indications of grave or systematic violations of rights set forth in the Convention. In accordance with article 8 (1) of the Optional Protocol and article 83 (1) of the Committee’s Rules of Procedure, the Committee decided to invite the Government of Mexico to cooperate with it in the examination of the information and, to that end, to submit its observations by 15 May 2003 (cf. letter from the Chairperson of the Committee, sent by the Secretary-General of the United Nations on 30 January 2003).

5. On 15 May 2003, through a note from the Permanent Mission of Mexico to the United Nations in New York, the Government of Mexico submitted its observations concerning the allegation made by the non-governmental organizations Casa Amiga and Equality Now. As well as providing detailed information about the issue, the Government of Mexico volunteered (i) to respond immediately to the request for additional information and, to that end, referred the Committee to the Under-Secretary for Global Issues of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; (ii) to invite the Committee to visit the country and to guarantee the conditions and facilities necessary to enable the inquiry to be conducted in total freedom; and (iii) its complete willingness to implement any recommendations adopted by the Committee after the inquiry. The Government of Mexico provided, inter alia, information about recent actions taken at the State, federal and legislative levels to address the situation in Ciudad Juárez.

6. On 3 June 2003, Casa Amiga, Equality Now and the Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights (it should be emphasized that the Mexican Committee provided relevant information to the Committee prior to the examination of Mexico’s fifth periodic report in August 2002) submitted additional information to the Committee, updating it about recent events that had allegedly taken place in Juárez. That information referred to the newly-discovered murders, the ongoing impunity of those responsible, threats directed towards those calling for justice for women, growing frustration on account of the authorities’ lack of due diligence in investigating and prosecuting the crimes in an appropriate manner and an emerging pattern of irregularities and incidents pointing to the possible complicity of the authorities in the continuing violence against women in Juárez. Reference was also made to a similar pattern of murders and disappearances involving women in Chihuahua City — a possible consequence of the impunity in Juárez and the spread of criminal activities. Attached to the information was the report of the Special Rapporteur on women’s rights of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), published in March 2003, following her visit to Mexico, which included a visit to Ciudad Juárez.

7. By means of notes verbales, dated 27 June and 7 July 2003, the Government of Mexico provided additional information which drew attention to recent results obtained in the investigations and details regarding the creation of a mechanism providing for coordination between federal bodies and civil society and its links with State and municipal institutions and the National Congress (Subcommittee of Coordination and Contact to Prevent and Sanction Violence against Women in Ciudad Juárez, chaired by the Minister for the Interior). That additional information from the Government also provided details of a planned 40-point action plan forming the basis of the Subcommittee’s monitoring activities: actions in the area of the promotion of justice; actions in the area of social development and actions to promote women’s human rights in Ciudad Juárez.

8. At its twenty-ninth session (July 2003), after having examined all the information submitted by the Government and taking into account the supplementary information provided by Casa Amiga, Equality Now and the Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights, the Committee decided to conduct a confidential inquiry under article 8 (2) of the Optional Protocol and article 84 of its Rules of Procedure and nominated two of its members, Ms. María Yolanda Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Maria Regina Tavares da Silva, to conduct the inquiry and report thereupon to the Committee. Lastly, the Committee decided to request the Government of Mexico, pursuant to article 8 (2) of the Optional Protocol and article 86 of the Rules of Procedure, to consent to a visit by the two members in October 2003 (the Government of Mexico was notified of that request by means of a note from the Secretary-General of the United Nations dated 11 August 2003). On 27 August 2003, the Government of Mexico consented to the visit of the two experts and made a commitment to provide all the assistance necessary to ensure that they could carry out their mission properly. Through that same note, Ms. Patricia Olamendi, Under-Secretary for Global Issues of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was confirmed as the representative of the Government of Mexico in accordance with article 85 (2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Committee. The Government agreed to the dates for the visit proposed by the Committee (18-26 October 2003). The two experts selected, Ms. María Yolanda Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Maria Regina Tavares da Silva, accompanied by two United Nations officials, Ms. Helga Klein and Mr. Renan Villacis, carried out the visit on the aforementioned dates.

II. Visit to Mexico, 18-26 October 2003

Activities of the members of the Committee during the visit

9. During their stay in Mexico, the members of the Committee visited the Federal District and State of Chihuahua (Chihuahua City and Ciudad Juárez).

10. In the Federal District, Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva conducted interviews with the following authorities: Ministry of the Interior (Head of the Human Rights Promotion and Protection Unit, Deputy Director-General of the Unit and Adviser to the Under-Secretary for Human Rights), Ministry of Development (SEDESOL) (Minister, Under-Secretary for Urban Development and Land Management and Director-General of the Institute), Federal Government Commissioner for the cases of women in Ciudad Juárez (appointed on 17 October 2003), Public Prosecutor’s Department/Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic and three Deputy Attorneys-General (Organized Crime, Regional Control, Protection and Criminal Proceedings and International Affairs) and the Directors-General of the Office of the Attorney-General (Crime Prevention, Victim Support), the National Women’s Institute (INMUJERES) (Chairperson of the Institute, Technical Secretary, Coordinator for Advisers and Deputy Director-General for International Affairs), National Human Rights Commission (Second General Representative), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Under-Secretary for Global Issues and Human Rights, Adviser to the Under-Secretary and Deputy Director-General of the Directorate-General of Human Rights).

11. The members of the Committee also met with nine representatives of the Ad Hoc Committee to Monitor the Murders of Women in Ciudad Juárez set up by the Senate and with five representatives of the Commission on Equity and Gender of the Chamber of Deputies — the two committees that form part of the National Congress of the Republic.

12. The members of the Committee had the opportunity to take part in a meeting of the Subcommission of Coordination and Contact to Prevent and Sanction Violence against Women in Ciudad Juárez, which brings together nine ministries/federal entities, the Public Prosecutor’s Department/Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic, the National Human Rights Commission and representatives of civil society.

13. The experts also met with United Nations bodies (the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM)) and non-governmental organizations (Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights and Milenio Feminista).

14. In the capital of the State of Chihuahua, the members of the Committee conducted interviews with the interim State Governor and Secretary-General of the Government, the Assistant State Public Prosecutor and the Director of Legal Affairs of the Office of the Public Prosecutor. They also called on the Head of the Chihuahua Women’s Institute.

15. In Ciudad Juárez, Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares da Silva held interviews with joint State/Federal, Federal and municipal authorities together with associations of the mothers of the women murdered or abducted in Ciudad Juárez or Ciudad Chihuahua, mothers of victims and representatives of civil society. They also visited sites where numerous victims’ bodies had been found in 2001 and 2002/3, sites of maquiladoras and the poorest areas of Ciudad Juárez.

16. The two experts conducted an interview with the Assistant State Public Prosecutor for the Northern Region, the Special State Prosecutor (Joint Office of the Prosecutor for the investigation of the murders of women), the Personal Assistant to the Mayor, the Representative of the Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic, the Head of the Federal Section of the Joint Agency for the Investigation of the Murders of Women and the General Coordinator for Human Rights and Citizen Participation of the Ministry of Public Security (Preventive Federal Police).

17. In Ciudad Juárez, the two experts also met with organizations of the victims’ relatives (Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, Justicia para Nuestras Hijas, Integración de Madres de Juárez), mothers of victims, local non-governmental organizations (Red Ciudadana No Violencia y Dignidad Humana, Casa Promoción Juvenil, Organización Popular Independiente, CETLAC, Grupo 8 de marzo and Sindicato de Telefonistas) and representatives of the local, national and international non-governmental organizations Casa Amiga, Equality Now and the Mexican Committee for the Defence and Promotion of Human Rights.

General conditions for the visit

18. The Government of Mexico was fully supportive of the visit and was cooperative throughout, respecting the confidential and independent nature of the investigation. It did everything necessary, both in Mexico City and in the State of Chihuahua, to ensure that the two experts conducting the investigation were able to complete the scheduled programme of work as effectively as possible and guaranteeing their security at all times. In particular, the two experts express their appreciation and gratitude for the excellent cooperation provided by the Mexican authorities with regard to logistics and to the provision of extensive and up-to-date oral and written information. They would also like to receive information concerning the mandate of the Commissioner, and about her functions and powers and other important matters which may arise and may be of interest, so that this information can be included in the report to be submitted to the Committee.

19. Ms. Ferrer Gómez and Ms. Tavares express their sincere thanks to all the representatives of civil society with whom they met during their visit. The extensive and concrete information freely provided during those meetings helped broaden their understanding and increase their knowledge of the present situation.

20. Lastly, they express their appreciation for the measures taken by the Federal authorities in Ciudad Juárez to provide protection for a member of a non-governmental organization involved in the case of the murdered and disappeared women in Ciudad Juárez, who was threatened during an incident that occurred during the experts’ visit. They express their desire to be kept informed of developments in this regard.

21. The two experts are very grateful to the Resident Coordinator/Representative of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and his colleagues, for their invaluable assistance, including all the logistical and technical facilities provided to the experts during preparations for the mission and during the visit to Mexico City and Ciudad Juárez.

III. Gender-based discrimination and violence - the situation in Ciudad Juárez

General context and evolution of the situation

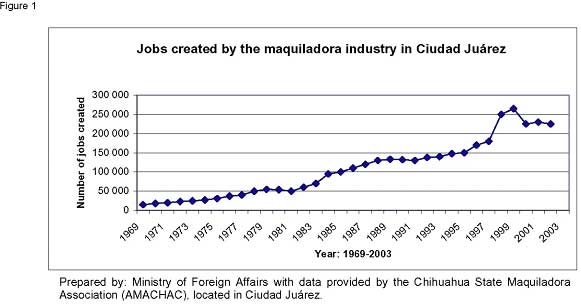

22. Ciudad Juárez lies in the northern part of the State of Chihuahua, on the border with the United States of America. With a current population of 1.5 million (including the floating population), it is the largest centre in the State of Chihuahua (Mexico’s “Big State”), accounting for 40 per cent of the State’s overall population. It includes an industrial sector that has seen dizzying growth, especially over the last decade, due to the growth of the maquila industry, which has brought an increase in the flow of migrants from other parts of Mexico, compounded by the presence of foreign migrants. Regarded as an “open door” to employment prospects and better opportunities, Cuidad Juárez is also an “open door” to illegal immigration and drug trafficking.

23. The accelerated population growth has not been accompanied by the creation of public services needed to respond to the basic needs of this population, such as health and education, housing, and sanitation and lighting infrastructures. This has helped create serious situations of destitution and poverty, accompanied by tensions within individual families and within society as a whole. During a visit to the city’s western district, the delegation was able to witness the extreme poverty of the local families; most of those households are headed by women and live in extreme destitution. Furthermore, the delegation was informed by various sources that in Ciudad Juárez there is a marked difference between social classes, with the existence of a minority of wealthy, powerful families, who own the land on which the marginal maquilas and urban districts are located, making structural change difficult. The overall situation has led to a range of criminal behaviours, including organized crime, drug trafficking, trafficking in women, undocumented migration, money-laundering, pornography, procuring, and the exploitation of prostitution.

24. All authorities consulted by the delegation recognize that the city’s erratic growth, together with a combination of social, economic and criminal factors, have resulted in a complex situation characterized by the rupture of the social fabric. One of its most significant aspects is the increase in violence in various forms, affecting the whole population — men, women and children. This rupture is also reflected in the acceptance of violence against women, which is regarded as a “normal” phenomenon within the context of systematic and generalized gender-based discrimination.

25. In addition, the situation created by the establishment of the maquilas and the creation of jobs mainly for women, without the creation of enough alternatives for men, has changed the traditional dynamic of relations between the sexes, which was characterized by gender inequality. This gives rise to a situation of conflict towards the women — especially the youngest — employed in the maquilas. This social change in women’s roles has not been accompanied by a change in traditionally patriarchal attitudes and mentalities, and thus the stereotyped view of men’s and women’s social roles has been perpetuated.

26. Within this context, a culture of impunity has taken root which facilitates and encourages terrible violations of human rights. Violence against women has also taken root, and has developed specific characteristics marked by hatred and misogyny. There have been widespread kidnappings, disappearances, rapes, mutilations and murders, especially over the past decade.

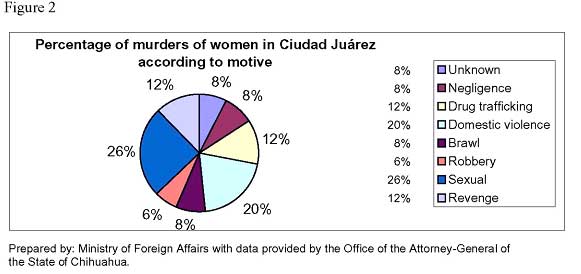

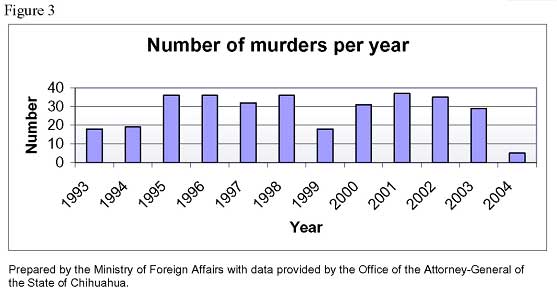

27. Although murders of women had occurred in Ciudad Juárez in previous years, it was in 1993 that the phenomenon intensified and started to become noticeable. In 1993, 25 women were murdered, according to information provided by the civil society organizations, which made the initial reports, and 18 murders according to Government sources based on a “newspaper survey” sponsored by the Chihuahua Women’s Institute.1 The murders increased rapidly in subsequent years, and in 1995 the first suspect, Abdel Omar Sharif, was arrested. During 1996 the murders continued, and members of the criminal group “Los Rebeldes” were arrested.

28. The situation continued to worsen, leading to the establishment, in 1998, of the Office of the Special Prosecutor for the investigation of the murders of women in Ciudad Juárez. Moreover, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) considered 36 of the murder cases and issued Recommendation 44/98, which found that the investigations conducted had “included actions violating the human rights of the women victims and their relatives. Also, international regulations and instruments had been violated, to the detriment of the aggrieved persons.” The same document acknowledges responsibilities and negligence on the part of the authorities and state agencies, specifically with regard to searching for and gathering of evidence, the determination of victims’ identity, and the delays in the processing of cases. The CNDH believes that not only are the human rights of the victims and their families being violated, but — more importantly — there has also been no consideration of the systematic pattern of violence demonstrated by the murders. It should be noted that some points of the Recommendation concerning the establishment of the criminal

_______________________

1 “Homicidios de mujeres: auditoria periodística” (January 1993-July 2003).

liability of State officials, at various levels, for negligence and grave omissions, were rejected by the State authorities.

29. The murders continued during 1999, extending to Chihuahua City, and some members of a new criminal group, “Los Ruteros”, were arrested.

30. At the same time, the international community began to become aware of the tragedy taking place in Ciudad Juárez. During the same year, the Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions visited Mexico and alerted the authorities to the insecurity and impunity reigning in the city and to the sexist nature of the crimes committed. Also, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women interviewed the Government concerning the specific murders of women that had occurred in Ciudad Juárez, and in 2001 the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers visited Mexico and addressed, among other matters, the question of the murders of women and the climate of impunity that surrounded them.

31. Finally, in 2002, in response to requests made by numerous individuals and organizations of civil society to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and its Special Rapporteur on Women’s Rights, the Federal Government invited her to visit the country — a visit that took place in February of that year. The following year, IACHR adopted and published a well-documented report, which presented an overall picture of the situation.2

32. Also in 2002, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women made a recommendation concerning the murders and disappearances in Ciudad Juárez, within the context of its consideration of the fifth periodic report of Mexico on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

33. At the level of Mexican State authorities, and especially the Federal level, the extent of the problem is gradually being understood in its various aspects. The Senate and the Chamber of Deputies have set up special commissions to consider the question of the murders and disappearances, and have on several occasions since 2000 suggested that cases be handled at the Federal level.

34. There is a gradual realization of the extent of the problem, as a phenomenon that goes beyond isolated cases in a structurally violent society. Under these circumstances, focusing solely on the murders and disappearances as isolated cases would not appear to be the answer in terms of resolving the underlying sociocultural problem. Along with combating crime, resolving the individual cases of murders and disappearances, finding and punishing those who are guilty, and providing support to the victims’ families, the root causes of gender violence in its structural dimension and in all its forms — whether domestic and intra-family violence or sexual violence and abuse, murders, kidnappings, and disappearances must be combated, specific policies on gender

_________________________

2 “Situación de los Derechos de la Mujer en Ciudad Juárez, México: el derecho a no ser objeto de violencia y discriminación”.

equality adopted and a gender perspective integrated into all public policies. This concept does appear to be on the political agenda, especially at the Federal level, but the authorities have been too slow in coming to terms with it, and it remains unclear whether such a process has occurred at all levels of authority.

Different forms of gender violence — data, characteristics and initial reactions

35. Having identified the underlying problem, some of the ways in which gender violence is occurring within the context of Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua City must be considered. First, the global data on the extent of the problem, provided by both non-governmental and governmental organizations, should be examined. The data do not tally, which is an issue addressed below.

36. According to the “newspaper survey” referred to above, which the experts received from various bodies, at both Federal and State levels, a total of 321 women were murdered between January 1993 and July 2003 in Ciudad Juárez. The Chihuahua Women’s Institute raised the figure to 326 during the experts’ visit, while the Chihuahua Interior Department, the Special Prosecutor and the representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Department/Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic all raised it to 328 during the same period. Other official sources, particularly the Public Prosecutor’s Department, had referred to 258 cases for the same geographical area up to the end of February 2003, while Amnesty International, in its August 2003 report, gives the figure of 370 murdered women in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua City. Furthermore, the non-governmental organizations visited by the delegation refer to a figure of 359 for the same area and period. With respect to the disappearances of women, too, the figures differ considerably, depending on whether the source is governmental or non-governmental. Whatever the true figure — and figures, although they are very important, are not the central issue — the primary point is the significance of these crimes as violation of women’s basic human rights and as the most “radical” expressions of gender-based discrimination.

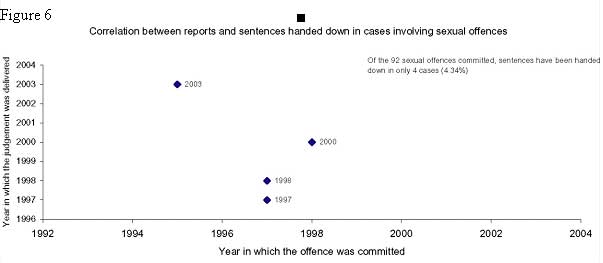

37. According to the authorities, the murders in Ciudad Juárez have different motives, including domestic and intra-family violence, drug trafficking, crimes of passion, quarrels, robbery, vengeance and sexual motives. And yet, a significant proportion of the murders — around one third — include a sexual violence component and similar characteristics. Here, too, the figures differ: the Chihuahua Women’s Institute refers to 90 cases, the Special Prosecutor and the PGR representative in Ciudad Juárez give 93, and non-governmental organizations 98. The victims of these crimes were raped or sexually abused and in some cases tortured or mutilated. The corpses were then abandoned on waste ground and eventually discovered by passers-by, not by the police.

38. As mentioned in other reports produced by national and international bodies, the women who have been murdered or have disappeared are young women of humble origins — maquila workers, students, or employees of commercial companies — who are abducted and kidnapped, and then either raped and murdered or made to “disappear”.

39. Suggested motivations for these types of crimes of specific violence against women have included drug trafficking, trafficking in organs, trafficking in women for purposes of sexual exploitation, or the production of violent videos.

40. The authorities’ response to the murders, disappearances and other forms of violence against women has been extremely inadequate, especially during the early 1990s, and even the Government accepts that there were errors and irregularities during that period. There are signs of a somewhat more positive attitude towards the prosecution and trial process, and indications that investigations are now proceeding more rapidly and with greater seriousness. However, in the most recent cases, despite evidence of an increased awareness of the seriousness of the facts, the state of the investigations is not entirely clear, and there are questions about the effectiveness of the legal process.

41. For example, the case of the eight corpses discovered in cotton fields in front of the Maquila Association in November 2001 led to public outrage and a massive protest, and gave rise to the “Campaign to stop impunity: not one murder more”. The State authorities insist that they carried out a rapid and immediate campaign by arresting the suspected culprits, in particular La foca (“the seal”) and El cerillo (“the match”). However, various individuals and groups contested those arrests, claiming that torture was used to extract confessions and, as a result, the individuals concerned later retracted their confessions. The suspicious death, while in detention, of one of the accused also fuelled the climate of doubt and mistrust in the legal process.

42. There also seems to be a tendency — especially among State authorities — to minimize the significance of these issues. In particular, some say that disproportionate attention is being paid to the situation in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua City, and note that violence against women in various forms, including domestic violence and violence within the family, and sexual violence, also exists in other Mexican cities and regions.

43. The experts were provided with a great deal of information by various sources concerning the obstruction of investigations, delays in searching for women who had disappeared, falsification of evidence, irregularities in procedures, pressure exerted on the mothers, negligence and complicity by State officials, the use of torture to extract confessions, and the harassment of relatives, human rights workers, and organizations of civil society who have been fighting for justice.

44. Within this brief general overview of the situation, mention should be made of the fundamental role played by organizations of civil society, groups working for victims’ relatives, and groups of human rights workers in consistently and persistently calling attention to the situation of the crimes and violations of the human rights of women in Ciudad Juárez and to the urgent need to ensure that justice is done in terms of finding and punishing those responsible. They awakened the consciousness of the national and international communities. Special mention should be made of the pressure applied by the IACHR and its Special Rapporteur on Women’s Rights, not only for the report it submitted, but also for the commitment won from the Mexican State to report regularly to IACHR over the past year.

Repetition of the phenomenon in other areas

45. Overall, despite the new level of awareness and the efforts made at various levels, the situation in Ciudad Juárez remains highly complex, tragic, prolonged, and full of unacceptable uncertainties, suspicions, and horrors.

46. Although it is considered that there has been a drop in the number of murders and disappearances in Ciudad Juárez over recent months, perhaps the result of the measures being taken to deal with the situation, especially by the Federal Government, in fact the same phenomenon of murders and disappearances — including cases of sexual violence, and with a similar pattern — have been occurring in Chihuahua City at an increasing rate.

47. The delegation was also provided with information by various sources concerning similar murders that have occurred recently in other regions of Mexico, specifically in Nogales, Tijuana, León, and Guadalaraja.

International commitments in the field of women’s rights

48. The primary progress in the situation lies in recognition that the problem exists and that an effective response, appropriate to the magnitude of the tragedy and to the obligations assumed by the Mexican Government with regard to the promotion and protection of women’s fundamental human rights, must be found.

49. The promotion and protection of human rights is one of the obligations which have been actively assumed by the current Government. Mexico has signed and ratified the principal international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Optional Protocol; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the Convention on the Rights of the Child; and, in the specific area of women’s rights, the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. It is also bound by relevant regional instruments.

50. In the context of such international obligations and, in particular, of the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, there have been serious lapses on the part of the Mexican State, specifically concerning articles 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 15 of the Convention.

51. Article 1 of the Convention states that “the term ‘discrimination against women’ shall mean any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women ... of human rights and fundamental freedoms ...” Gender-based violence constitutes an exclusion and restriction which impedes the enjoyment of their fundamental rights. This is confirmed in the Committee’s Recommendation No. 19, which states that “the definition of discrimination includes gender-based violence, that is, violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman ...” and that “gender-based violence is a form of discrimination that seriously inhibits women’s ability to enjoy rights and freedoms ...”.

52. The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1993, also states that “the term ‘violence against’ women means any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life”.

53. As will be clear from the following, the situation in Ciudad Juárez — gender-based violence and the resulting impunity — results in a clear violation of the provisions of the Convention.

54. Article 2 recognizes the responsibility of States to follow a policy of eliminating discrimination against women. To that end, they undertake “to adopt appropriate legislative and other measures, including sanctions where appropriate, prohibiting all discrimination against women”; “to establish legal protection of the rights of women ... and to ensure through competent national tribunals and other public institutions the effective protection of women against any act of discrimination”; “to refrain from engaging in any act or practice of discrimination against women and to ensure that public authorities and institutions shall act in conformity with this obligation”; and “to take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which constitute discrimination against women”.

55. It is clear that there have been lapses and violations in the State’s fulfilment of its obligations in those areas. While there is now a greater political will, especially on the part of Federal agencies, to deal with discrimination and violence against women, it must be said that the policies adopted and the measures taken since 1993 in the areas of prevention, investigation and punishment of crimes of violence against women have been ineffective and have fostered a climate of impunity and lack of confidence in the justice system which are incompatible with the duties of the State.

56. Under article 5 of the Convention, States Parties are required to take appropriate measures “to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women”.

57. This obligation of the State has not been duly fulfilled; even the campaigns aimed at preventing violence in Ciudad Juárez have focused not on promoting social responsibility, change in social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women and women’s dignity, but on making potential victims responsible for their own protection by maintaining traditional cultural stereotypes.

58. Similar observations could be made regarding article 6, which establishes the obligation “to suppress all forms of traffic in women and exploitation of prostitution of women” — a possible motive for the murders and disappearances which has been neither confirmed nor denied — and article 15, which states that “States Parties shall accord to women equality with men before the law” in all aspects of life and, specifically, establishes the right to the free “movement of persons”.

59. This is not the case in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua City, where a climate of fear and danger prevents many women, especially young women and women from the lower social classes, from freely leading normal lives. Furthermore, although the right to equality before the law is guaranteed in article 4 of the Mexican Constitution, it has not been, and is not being, guaranteed to women in the relevant proceedings carried out in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua City.

60. All of this shows that there are serious lapses, which it is urgent to remedy, in the Mexican Government’s fulfilment of its responsibilities as a State Party to the Convention.

IV. Murders and disappearances

Principal problems

Profile of the murdered and disappeared persons

61. Although, as has been shown, there are no really reliable statistics, most official sources agree that over 320 women have been murdered in Ciudad Juárez (the civil society organizations with which the delegation met maintain that there are 359 victims); one third of them have been brutally raped.

62. Violence against women has increased steadily during the past decade with a consequent rise in the number of murders motivated by sex, domestic problems and disputes or drug trafficking and use.

63. Generally speaking, the victims of crimes of sexual violence are pretty, very young women, including adolescents, living in conditions of poverty and vulnerability; most of them are workers in maquilas or at other jobs or are students.

64. For many years, these victims disappeared while on their way to or from their homes since they had to cross deserted, unlit areas at night or in the early morning. Now, these disappearances take place in broad daylight in the city centre, escaping police notice and with no one reporting having seen anything unusual.

65. As far as we know, the method of these sexual crimes begins with the victims’ abduction through deception or by force. They are held captive and subjected to sexual abuse, including rape and, in some cases, torture until they are murdered; their bodies are then abandoned in some deserted spot.

66. As stated above, they are murdered because they are women and because they are poor. Since these are gender-based crimes, they have been tolerated for years by the authorities with total indifference. It is also alarming to learn that the problem is spreading under similar conditions to other cities in Mexico.

67. Some high-level officials of Chihuahua state and Ciudad Juárez have gone so far as to publicly blame the victims themselves for their fate, attributing it to their manner of dress, the place in which they worked, their conduct, the fact that they were walking alone, or parental neglect; this has provoked justifiable indignation and highly vocal criticism.

68. The current Governor of Chihuahua state told the delegation that while a murder in Juárez causes a major scandal, such things happen all over Mexico and are far more common in the United States.

Circumstances in which the bodies are found

69. It is significant that in the crimes of sexual violence — during the past decade — the women’s bodies have nearly always been found in the same deserted areas, which can only be reached by helicopter or four-wheel-drive vehicles. They are found when someone happens to pass by and reports them; the bodies have never been found as a result of investigation by the Public Prosecutor’s Department/Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic.

70. Some of the victims have been shackled, beaten or tortured. Several of them have been mutilated; many were in an advanced state of decomposition; some were wearing clothes or were found with objects belonging to other women; and, in some cases, only the bones of victims who had disappeared years previously or, inexplicably, of girls who had spent years or months in the hands of their captors have been found. Some relatives also told the delegation they had heard that some bodies had been frozen for a period of time.

71. Far from hiding their victims, the murderers leave them in plain sight, perhaps as a challenge to the authorities since they have enjoyed total impunity thus far. By a curious coincidence, the discoveries of murdered youths have also coincided with the announcement of Government measures or actions taken by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as if they were a response by or a threat from the criminals.

72. It is noteworthy that, according to several of the mothers mentioned above, they or their relatives saw their daughters’ dead bodies with hair and skin; several days later, only bones remained. Some of them also received sealed coffins which the authorities did not allow them to open.

The disappeared

73. It is impossible even to guess how many women have actually disappeared in Ciudad Juárez during the past decade; the current estimate varies from the 44 acknowledged by the State authorities to the 400 mentioned by NGOs and the 4,500 reported by the National Human Rights Commission.

74. The Government maintains that most cases do not really involve disappearances since a high percentage of the women working and living in Ciudad Juárez are from other parts of the country. Thus, they stay for a while and then leave; many go to the United States, leave with their boyfriends, run away after serious disagreements with their parents or flee from domestic violence. In addition, disappearance is not considered a crime in Mexico.

75. For these reasons, the authorities do not immediately investigate the cases which are reported and do not consider themselves obligated to act on reports of abduction; instead, they tell the disappeared persons’ families to look for them and to make inquiries; days pass before an investigation is opened. In reality, according to civil society organizations and the victims’ families, nothing is done and essential time, during which lives could be saved, is lost since there is evidence that the girls always remain in their killers’ hands for several days before they are murdered.

76. There are many witnesses to the authorities’ indifference to the desperation of families who report a disappearance; despite numerous attempts, they have failed to convince the appropriate agencies to open investigations. Days have passed without action being taken, and they have been told to look into the matter on their own. Even the Head of the Chihuahua Women’s Institute said that families are kept waiting for hours before being interviewed.

77. Two of the many examples of this laziness and inertia speak for themselves:

78. In 1995, Cecilia Covarrubias Aguilar, aged 15, left home to take her newborn daughter to the hospital; both mother and baby disappeared. Her body was found some time later, but eight years passed before the little girl’s whereabouts were known.

79. After searching constantly, her mother, Soledad Aguilar, found a child whom she believes to be her granddaughter and requested DNA testing; she was informed that the results were negative. On rereading the report, she later saw from the photographs that the authorities had replaced the little girl with another child. Despite her repeated requests, the little girl’s footprints have not been compared with those taken from her granddaughter at birth. The local authorities have recommended that she should try to reach an agreement with the family in question.

80. Lydia Alejandra García Andrade disappeared on 2 February 2001. Her mother, Norma Andrade, filed a report on 16 February and was rudely told that her daughter must have run away with a boyfriend. She informed the delegation that two days later, at 9 p.m., a woman had called the police emergency number and reported that in front of her house, a young woman in a white car, naked from the waist down except for her socks, was being beaten. The car was parked there for an hour and a half but the police did not arrive until 11 p.m., by which time she had already been taken away. Her mother called a television station, told her story and said she hoped that there would not be another dead girl.

81. Lydia Andrade’s body was later found. In August 2001, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) informed the police that they knew where she had been held, what had been done to her and why she had been murdered but, inexplicably, that information was leaked to the press and published and the accused fled. The police waited two months before checking the place in question.

82. The young woman’s mother said that the autopsy had been incomplete. Pubic and other hair had been found on her body but had not been sent for analysis and she had been gang-raped. Her case is riddled with irregularities.

83. Both the Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic and the Special Prosecutor in Ciudad Juárez have reported that they are implementing a new system for classifying disappearances so that cases defined as “high risk” can be investigated immediately.

84. It is considered that a disappearance is high risk and should be investigated by the Office of the Special Prosecutor for the investigation of the murders of women if it is certain that they had no reason to leave their homes, if the disappearance occurred on the victim’s way to or from school or if the victim is a young girl; these criteria exclude girls whose conduct is reprehensible or who have family problems.

85. The Head of the Chihuahua Women’s Institute told the experts that although there have been changes since January 2003, only one squad is available and that in some cases, when a case of disappearance is reported, it cannot be investigated for five or six days even though immediate action is called for.

86. The authorities stated that cases which were not considered high risk were also investigated through the victims’ unit of the Office of the Special Prosecutor for Sex Crimes and Crimes against the Family.

Investigations and trials

87. Thus far, in the cases involving sex crimes, the murderers have acted with full impunity. Nearly all sources, including statements and comments made to the experts by Federal Government officials, the heads of federal agencies and several senators, have made it clear that the local authorities, both state and municipal, are assumed to have a years-long history of complicity and fabrication of cases against the alleged perpetrators.

88. On numerous occasions, civil society organizations and the victims’ relatives criticized the shortcomings in the criminal justice system, maintaining that no case of homicide linked to sexual violence was investigated in depth, the scene of the crime was not preserved, evidence was destroyed, accusations were ignored, defendants were framed, evidence was lost, pages were removed from files, and some of them have only a few pages, indicating that years had gone by without any investigation whatsoever. They claim that greater importance seems to have been attached to the victims’ private lives in an effort to justify the murders.

89. As an example, they cited the case of young Verónica Castro, who had been abducted and raped by police and then escaped and lodged a complaint against the bodyguard of the Chief of the Prosecutor’s Office and two federal police officers, who were not even arrested and are now said to be no longer working in that unit.

90. In another case, which will be referred to later, it was reported that the day after the victims were found, the ground was dug up in the vicinity of the discovery, apparently to conceal any evidence.

91. The authorities in various entities argue that, for a long time, resources, training or experienced personnel were lacking.

92. The delegation was informed in official meetings at the federal, state and local level that protocols have begun to be implemented on how to handle the scene of the crime and the evidence, as well as specific manuals in all specialized areas, on which action is guaranteed because their application is mandatory. Resources of all kinds have also been allocated to guarantee that any necessary investigations will be conducted. The so-called “cold cases” concerning victims found between 1993 and 1997 have been reopened.

93. The Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic has exercised its power to take over 14 cases in which women were murdered, in response to a complaint and a person who turned himself in, linking them to organized crime. Of those victims, eight were found in the cotton fields in November 2001 and six, in Cristo Negro, three in November 2002 and three in February 2003.

94. At the meeting in the Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic, in referring to the case in the cotton field, it was said that after carrying out an investigation, they had determined that the persons in custody were not guilty, adding that the problem would not be solved simply on the basis of the file. They recognized that there were clues hinting at a possible cover-up by elements of the municipal police.

95. In this connection, during a meeting held with Casa Amiga and Equality Now, an official involved in the case of the dead women found in the cotton field told the delegation that when they were in the process of identifying the victims, the investigation had been closed and the identities of the girls who had been murdered was disclosed without testimony from expert witnesses. Only days later, two people had already been arrested. When the DNA tests were done eight months later, only three corpses matched the initial identification.

96. He also said that in Ciudad Juárez, no investigation had been carried out, that there had been complicity, direct or indirect protection of the accused, and that there was a pattern of denying the problem, minimizing it, discrediting the victims, blaming them for their own fate and framing the accused.

97. In the same vein, a former Director of the Cerezo Prison in Ciudad Juárez testified during this meeting, and said that, being thoroughly familiar with both the criminals and the police, he was convinced that there had been complicity and a common interest between them and that they had agreed to protect drug dealers. He had noted that in the case of “los Rebeldes”, accused of the murder of “Lomas de Poleo”, there had been confessions under torture, which he confirmed in filing complaints to the National Human Rights Commission. He also said that it was not certain that Omar Latif Sharif, being in prison, had had any contact with them, or had been giving them instructions or paying them for the murders which were committed. When he was prison director, Sharif had been under his custody, isolated and under permanent surveillance, as he was convinced there was a very great chance he would escape. He had never been called to testify. In his view, the State judicial police had something to do with the murders and they were therefore trying to prevent the federal authorities from participating in the investigations.

98. The Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic said other avenues of investigation were being pursued in the cases it had taken over. Although no direct links among the victims have been determined thus far, some were at the same school or appeared in the same place and they are going to be studied one by one. Other circumstantial evidence will be analysed as well. Also, one of the statements is pointing to elements of the municipal police.

99. On 14 August, the Attorney-General’s Office for the State of Chihuahua and the Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic joined forces to carry out investigations as the Joint Investigating and Prosecuting Agency in Ciudad Juárez.

100. The Office of the Attorney-General of the Republic is doing an inquiry into 45 prior cases from the State Attorney-General’s Office in order to determine whether these cases come under federal jurisdiction, propose appropriate action and identify, arrest and prosecute the accused. The common denominator of all these cases is that the women’s murders were sexually motivated.

101. It was explained to the experts that they are systematizing all the information on the murders of the women in Ciudad Juárez, utilizing an updated data analysis system that will enable the institution’s intelligence unit to support the Public Prosecutor’s Office by processing information on past and present cases and even future profiles with a view to strengthening their action and improving the efficiency of the justice system. At the time of our visit, information contained in 34.5 per cent of the 224 files that had been found was already in the database.

102. They said they were at the stage of reviewing all the trials, and were prepared to reopen them or establish new avenues of investigation and that they would demand strict accountability in what would be a full-scale review, albeit with limitations, since, in many cases, the past had to be reconstructed.

103. Nonetheless, according to an explanation that was later given to the experts in Ciudad Juárez when they visited the local office of the Attorney-General of the Republic, what is actually happening is that since the files, which are incomplete or have problems, do not come under federal jurisdiction, when they are reviewed, they are returned for follow-up to the Office of the Special Prosecutor for the investigation of the murders of women, in other words, everything goes back to square one.

104. There is a consensus among all sources, including the three levels of Government, that, being a border town, both Mexican and United States citizens could be implicated in the crimes, that the murderers might even live there and be involved in drug dealing, commit the murders in the United States and then bring the victims to Ciudad Juárez.

105. Hence, in the middle of the year, the Government of Mexico began asking the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for specialized technical support and advice. Cooperation was established for purposes of training and implementing a specific programme for violent crimes.

106. Civil society organizations which met with the delegations called for a binational convention to investigate crimes against women. They felt that it was inconceivable that there should be one on car thefts but not on horrific murders.

107. They said that in Ciudad Juárez, trials are not public and are frequently transferred to Chihuahua, which creates huge difficulties for families with no resources. The local authorities justify this decision by arguing that the Cerezo jail is overcrowded and that to be imprisoned in Chihuahua, they have to be tried there. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), however, believe they are taken to Chihuahua because the Juárez prison allows visits and interviews with the press.

108. In the cases linked to domestic violence or common crime, the Government maintains that progress has been made in the investigation, identification and prosecution of the accused, and according to the authorities, most of those convicted have been sentenced to more than 20 years in prison.

109. This does not occur in acts of sexual violence. There are persons who are imprisoned for seven years, others for five and, although the Law establishes that the term of the sentence should be two years, files are sometimes incomplete and the judges are not convinced by the evidence. They may therefore order a retrial and go back to the beginning.

110. At the request of the Government of Mexico, a United Nations expert mission visited Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua and Mexico, D.F. in September, in order to carry out a study and provide technical advice on technical legal measures, the discovery period and expert witnesses with a view to strengthening the ministerial and investigative procedures in cases where women are murdered.

Hostile attitude towards family members and the situation they face. Threats and defamation directed towards civil society organizations

111. The meeting with a group of mothers of victims of murders and sexual violence was genuinely moving and powerful. It is inconceivable that people should be so dehumanized and that people who are so humble and battered by life, far from being supported and comforted, are mistreated and even threatened and harassed. The experts heard testimony exposing very serious arbitrariness and irregularities. Only a few examples will suffice to illustrate this.

112. Josefina González (mother of Claudia Ivette González), her daughter, disappeared on 10 October 2001 while returning from the maquila, as she had arrived two minutes late and they would not let her in. She was found the following month, on 6 November, in the cotton field. She was unrecognizable, but they told her it was her daughter; however, when she saw her, she was a skeleton and she wondered what they had done with her skin and her hair if only eight days had passed and the body was intact, but they told her she had been eaten by animals. The police cordoned off the entire area and said that they had cleaned it; however, several days later, they found her wet overalls, her voter card and her maquila apron. This makes her mother live in doubt. One year later, they returned the body but did not transmit the results of the DNA tests, claiming they had been lost. She requested the file and it was not given to her because she had to pay 1,000 pesos, which she did not have.

113. Ramona Rivera is the mother of Silvia Elena Rivera, who disappeared in July 1995. She lodged a complaint but was told she had to wait 72 hours; they told her to look for her herself and keep them informed. On 1 September, a patrol came to her house and informed her that her daughter had been found. She was very happy. They did not allow her son to accompany her, telling him they would bring her back later. They brought her to the area where the body had been found and, when she saw her, she recognized some of her clothes. It was then that she knew she was dead. They did not bring her back because “they had a lot to do” and she had to beg in the street to be able to return home. The crime was attributed to Sharif, who was already in prison. She goes there every month to see if there is any update on the culprits but they tell her that her case is very old.

114. Norma Andrade is the mother of Lidia Alejandra, whose case we referred to in the section on the Disappeared. Like other grandmothers, she is requesting that the processes required for adoption of her grandchildren be completed, since, in accordance with Mexican legislation, even though she is their guardian and they depend on her, she is not entitled to the subsidies given to working mothers.

115. According to testimony by the Ministry of Social Development, “Under the legal system, when a woman dies, her orphan children placed with their grandparents cannot be legally recognized by them. Hence, an adoption process must be initiated.”

116. It is typical of the general insensitivity there that this lady was threatened by the police who went to her house that she would be arrested if she did not appear in response to a summons to the Municipal Procurator’s Office, despite the fact that they were aware of the serious condition of her husband, who died 20 days later. When she did go, she found out that the purpose was to give her her daughter’s file.